A Look at the World’s Most ‘Cursed’ Jewels

As Halloween approaches, Associate Editor Lenore Fedow haunts us with the stories of four cursed jewels and shares a lesson in karma.

I’ve written about cursed jewelry previously in a 2019 story, detailing the more well-known “cursed” jewels, like the Koh-i-Noor Diamond and the Hope Diamond.

I also held a webinar last October about gemstone lore and legends with jewelry designer Alexandra Lozier where we delved into “bad luck” opals, talismans, and more.

Jewelry and storytelling go hand in hand, so I still have a few stories left to share this Halloween.

The Delhi Purple Sapphire

A common thread in these stories of allegedly cursed gemstones is a simple morality tale—someone took something that didn’t belong to them and bad luck followed.

The story of the Delhi purple sapphire follows this classic pattern.

For starters, it’s not a purple sapphire at all. It’s an amethyst. (If you’re going to rob a precious gem, then at least have the decency to know what you’re stealing.)

A curator and amethyst fan from the Natural History Museum in London, where the stone now resides, shared the tale in a 2013 blog post after consulting with the museum’s mineral curators.

It’s said that a British soldier stole the stone from the Temple of Indra, the Hindu god of war and weather, during the Indian Mutiny of 1857 in Kanpur, India.

The stolen loot made its way into the hands of Colonel W. Ferris of the Bengal Cavalry, who took it back to England.

The gemstone was said to be nothing but trouble from the start, plaguing the colonel’s family with health issues and financial worries.

The “sapphire” was passed down to the colonel’s son who gave it to scientist and writer Edward Heron-Allen in 1890. Heron-Allen joined the chorus of those declaring the stone to be bad news.

In a 1904 letter, he described his experience of owning the Delhi purple sapphire and how it haunted him and others.

Looking to un-curse the violet stone, he tried giving it a makeover by surrounding it with good luck symbols.

He set the stone in a silver snake ring, said to have belonged to Heydon the Astrologer, a 17th century English occultist philosopher, and added zodiac symbol plaques and two pendants, one a silver Tau symbol and the other holding two amethyst scarabs.

The redesign didn’t work.

Heron-Allen wrote that he, his wife, and others were haunted by a “Hindu figure” who wandered his library demanding the stone back.

“He sits on his heels in a corner of the room, digging in the floor with his hands, as if searching for it,” he wrote. Creepy!

Heron-Allen tried to get rid of the gemstone by gifting it to friends, but the bad luck continued.

After the first friend returned it, he threw it into the Regent’s Canal, but it made its way back to him after a dredger found it.

He gifted it to another friend, an opera singer, who then lost her voice. The story goes that she never sang again, and the stone was once again in Heron-Allen’s hands.

He couldn’t shake the stone, but I bet he lost a lot of friends.

When his daughter was born, Heron-Allen packed the gemstone up in seven boxes, put it in a safety deposit box, and sealed it with a warning letter inside.

He asked that the Delhi purple sapphire not see the light of day again until 33 years after his death.

His daughter didn’t wait that long, gifting the stone to the Natural History Museum in London just a year after his death, where it remains to this day.

Heron-Allen had some parting words of advice in his letter.

“This stone is trebly accursed and is stained with blood, and the dishonor of everyone who has ever owned it,” he wrote.

“Whoever shall open [the box], shall first read this warning, and then do so as he pleases with the jewel. My advice to him or her is to cast it into the sea.”

It may be less that the stone was haunted and more that Heron-Allen was telling tall tales to give some credence to a 1921 short story he wrote, called “The Purple Sapphire,” under the pseudonym Christopher Blayre.

Museum experts think he may have pieced the story of the cursed gemstone together from other stories he’d heard over the course of his life and then had the good luck amulet made to back it up.

Still, people have reached out to the museum to corroborate the legend based on what they’ve found in their own family histories.

If you ask me, lock up this allegedly cursed gemstone and throw away the key.

The Delhi Purple Sapphire is still in the museum’s possession, but is no longer on display.

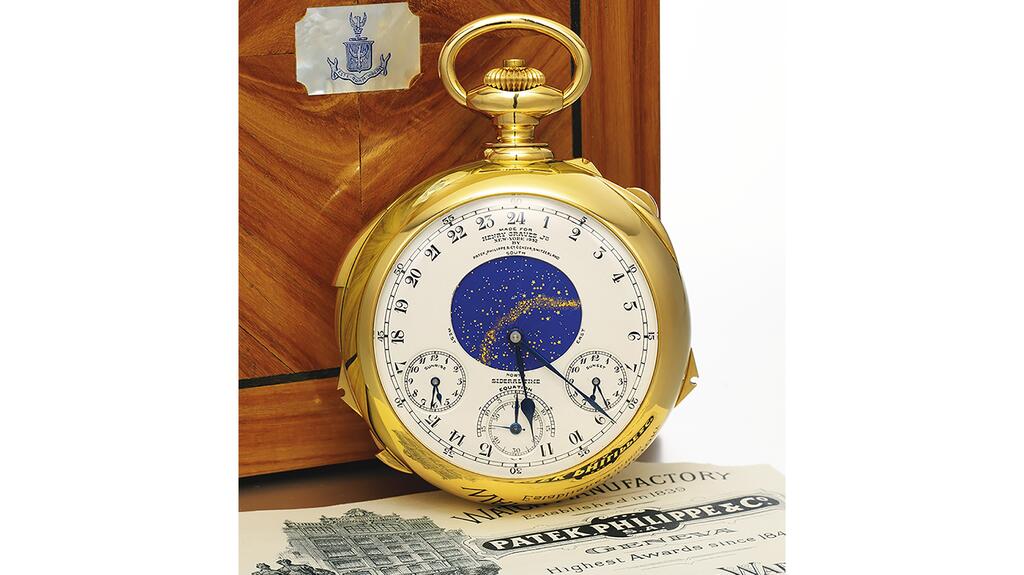

Graves Supercomplication

I don’t write about watches often, and never about haunted watches, but there’s a first time for everything. We can’t let jewelry have all the fun.

SEE: The “Cursed” Graves Supercomplication

The story of this watch starts with the story of two rich guys competing to see who could own the coolest watch.

The first man was American businessman Henry Graves, who had made a fortune in banking and the railroads. He was old-money rich, descended from John Graves, who helped to settle Concord, Massachusetts in 1635.

His competitor was automobile tycoon James Ward Packard.

The two men both frequented Patek Philippe and went back and forth ordering more and more complex watches, according to a recounting of the history by Alan Banbery, the former curator of the Patek Philippe Museum.

In 1925, looking for the competitive edge, Graves commissioned a watch with a staggering 24 complications. The Graves Supercomplication was born.

Created by Patek Philippe, it is said to be the world’s most complicated mechanical watch made without the use of computer technology. It took seven years to research, develop, and produce the one-of-a-kind timepiece.

The watch weighs more than 1 pound, consisting of 920 individual components, including 430 screws, 110 wheels, 120 mechanical levers and parts, and 70 jewels.

Graves paid $15,000 for the watch at the time, which is about $311,500 in today’s money.

The watch is a beauty and a technical masterpiece.

My favorite feature is that on one side of the double dial is an aperture of the night sky over Central Park. The celestial chart shows the accurate spacing between the stars and their magnitude.

Though it took seven years to make, the Graves Supercomplication took no time at all to wreak havoc.

Soon after receiving the watch, Graves’ best friend died, followed by the tragic death of Graves’ son in a car crash.

Graves died in 1953 and the watch was passed along to family members, seemingly without incident.

It was sold at auction in 1999 to Sheikh Saud bin Muhammed al-Thani, a member of the Qatari Royal Family. The sheikh was a notable frequenter of auction houses, though less eager to pay his debts.

He owed millions of pounds in unpaid invoices and, following a long legal dispute, his assets were frozen by the High Court in London, as per a New York Times article.

In need of some cash, he gave the watch to Sotheby’s in 2014 to be auctioned.

Two days before the watch was sold for $15 million, Sheikh Saud bin Muhammed al-Thani, 48, died suddenly.

Is it possible this watch is haunted? Sure, but I see the curse of greed at work here.

The Graves Supercomplication is a product of the fierce competition between two insanely wealthy men at a time when droves of people were standing in bread lines, fighting for the bare necessities amid the Great Depression.

And when it fell into the hands of a wealthy individual who refused to pay his debts, the watch struck again.

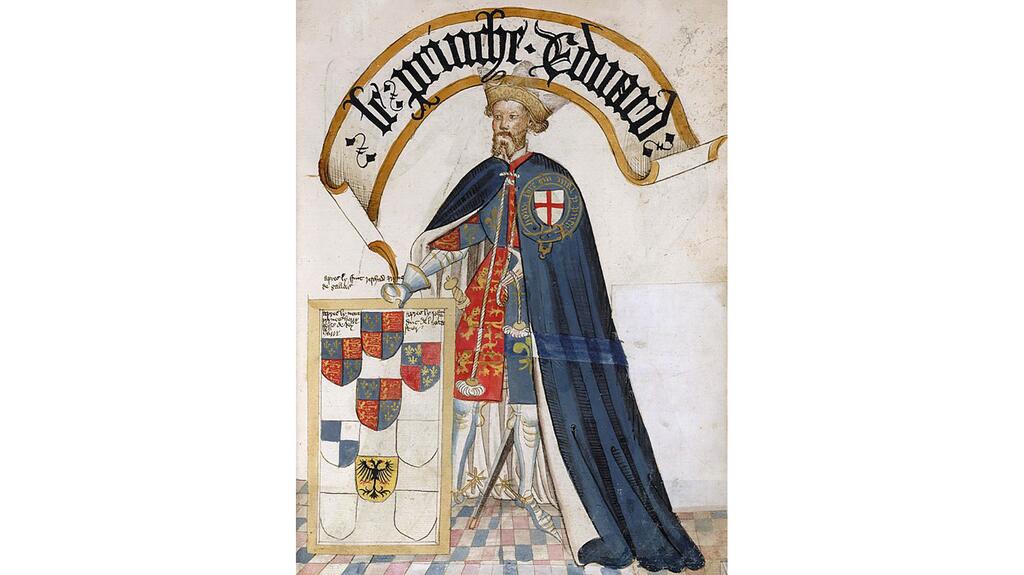

The Black Prince’s Ruby

What a great name for a cursed gemstone.

Similar to the Delhi Purple Sapphire, this ruby isn’t a ruby at all.

It’s a 170-carat cabochon spinel, thought to have been mined in the mountains of Afghanistan, according to GIA.

The first mention of it was in the 14th century when the aptly named Don Pedro the Cruel of Seville, Spain, stabbed Abu Sai’d, the Moorish Prince of Granada, to death and ransacked his corpse, stealing the red stone, according to Diamond Buzz, a jewelry-focused educational blog.

I will repeat again that we really shouldn’t be stealing things. Ditto on the murder part.

And so the curse was born. The gemstone was said to bring bad luck and untimely death to all who touch it.

The spinel found its way to Edward of Woodstock, known as “The Black Prince,” who was famous for his battlefield victories during the Hundred Years’ War.

Historians argue about the origin of his nickname, but many attribute it to his brutal attack on the French town of Limoges in September 1370, in which thousands of men, women, and children died.

The Black Prince died before he could assume the throne.

The stone then fell in the hands of King Henry V, who wore it on his battle helmet when he defeated the French at the Battle of Agincourt.

Many British royals have owned the stone, including King Henry VII and his daughter, Queen Elizabeth I.

The gem has seen more than its fair share of bloodshed and has been around for quite a number of unfortunate deaths within the Royal Family.

King Charles I held the stone until he was beheaded in 1649 for treason and it was sold.

Charles II bought the stone back, but the battle continued, and it was nearly stolen by Irish colonel Thomas Blood in 1671 when he attempted to steal the crown jewels from the Tower of London.

The “ruby” now sits front and center on the Imperial State Crown of England.

I believe that inanimate objects can hold negative energy, whether it be a cursed gemstone or a house where something unthinkable happened.

I would also posit that you can’t colonize half the world like it’s your personal playground for generations and then expect the good luck gods to smile down upon your family.

But sure, let’s blame the spinel.

The Lydian Hoard

We’ve made it to our last cursed jewels of the day and I’m starting to feel like a broken record.

Stop. Taking. Things. That. Don’t. Belong. To. You.

If I had been around in the 1960s, that’s what I would have said to the group of villagers who uncovered and raided the burial chamber of a princess from the ancient kingdom of Lydia in the Usak region of western Turkey.

Inside the chamber were 363 gold and silver artifacts, like jewelry and coins, dating back to the 6th century B.C, according to “Ancient Treasures: The Discovery of Lost Hoards, Sunken Ships, Buried Vaults, and Other Long-Forgotten Artifacts,” a 2013 book by Brian Haughton.

It’s known as the Lydian Hoard, or the Karun Treasures.

Lydia established strong trade networks and sat at a crossroads of cultures, and so the artifacts show both Eastern and Greek influences.

An important source of its wealth was the gold found in the Pactolus River near the civilization’s capital. Lydians used this gold to create some of the world’s first coins, wrote Haughton.

Artifacts from this ancient civilization are few and far between, so every piece is valuable in a literal and historical sense.

But neither respect for the dead nor an appreciation of history are any match for the almighty dollar.

The princess’ tomb was ransacked and the pieces were sold to a shady antiquities dealer, who later sold the goods to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

A UNESCO agreement in 1970 banned the illegal export of cultural property, but this transaction slipped in right under the buzzer.

Some of the pieces were put on permanent display in 1984, though not with the correct provenance, a fact that did not escape the notice of Turkish authorities.

In 1986, Turkey demanded the pieces be returned, but the Met refused. The following year, Turkey filed a lawsuit.

In her book, “Loot: The Battle Over the Stolen Treasures of the Ancient World,” author Sharon Waxman shared some insight on the case.

The Met tried to have the lawsuit dismissed, but when third-party scholars began their research, the evidence was damning.

“Wall paintings were measured and found to fit the gaps in the walls of one tomb. Looters cooperating with the investigation described pieces they had stolen that matched the cache at the Met,” wrote Waxman.

By 1993, years into this long legal battle, the Met agreed to settle the dispute and returned the Lydian Hoard to Turkey to be put on display in the Usak Museum.

One of the most notable pieces was a gold brooch featuring a hippocampus, a mythical winged sea-horse, seen above.

We can safely bet The Met was cursed with incredibly expensive legal fees, but what happened to the villagers who uncovered the treasure?

The story goes that none of them were able to enjoy their ill-gotten gains, living through great misfortune and dying violent deaths.

The Lesson We Can’t Seem to Learn

The more I research “cursed” jewelry, the more I think the real curse may be karma.

The thought reminds me of a favorite quote, attributed to the legendary author James Baldwin.

“People pay for what they do, and still more for what they have allowed themselves to become. And they pay for it very simply; by the lives they lead.”

It’s easier, and more interesting, to believe it’s a stone that has cursed us rather than that our actions have consequences.

That’s not to say every bad thing that happens to us is karmic payback, but none of these stones were “cursed” out of nowhere.

You get back what you put in and the “cursed” put a lot of bad into the world, whether that be warfare or greed.

As Halloween approaches, with its ghosts and goblins in tow, keep in mind that, sometimes, the real monsters look just like you and me.

The Latest

Prosecutors say the man attended arts and craft fairs claiming he was a third-generation jeweler who was a member of the Pueblo tribe.

New CEO Berta de Pablos-Barbier shared her priorities for the Danish jewelry company this year as part of its fourth-quarter results.

Our Piece of the Week picks are these bespoke rings the “Wuthering Heights” stars have been spotted wearing during the film’s press tour.

Launched in 2023, the program will help the passing of knowledge between generations and alleviate the shortage of bench jewelers.

The introduction of platinum plating will reduce its reliance on silver amid volatile price swings, said Pandora.

It would be the third impairment charge in three years on De Beers Group, which continues to grapple with a “challenging” diamond market.

The Omaha jewelry store’s multi-million-dollar renovation is scheduled to begin in mid-May and take about six months.

Criminals are using cell jammers to disable alarms, but new technology like JamAlert™ can stop them.

The “Paradise Amethyst” collection focuses on amethyst, pink tourmaline, garnet, and 18-karat yellow gold beads.

The retailer credited its Roberto Coin campaign, in part, for boosting its North America sales.

Sherry Smith unpacks independent retailers’ January performance and gives tips for navigating the slow-growth year ahead.

From how to get an invoice paid to getting merchandise returned, JVC’s Sara Yood answers some complex questions.

Amethyst, the birthstone for February, is a gemstone to watch this year with its rich purple hue and affordable price point.

The Italian jewelry company appointed Matteo Cuelli to the newly created role.

The manufacturer said the changes are designed to improve speed, reliability, innovation, and service.

President Trump said he has reached a trade deal with India, which, when made official, will bring relief to the country’s diamond industry.

The designer’s latest collection takes inspiration from her classic designs, reimagining the motifs in new forms.

The watchmaker moved its U.S. headquarters to a space it said fosters creativity and forward-thinking solutions in Jersey City, New Jersey.

The company also announced a new partnership with GemGuide and the pending launch of an education-focused membership program.

IGI is buying the colored gemstone grading laboratory through IGI USA, and AGL will continue to operate as its own brand.

The Texas jeweler said its team is “incredibly resilient” and thanked its community for showing support.

The medals feature a split-texture design highlighting the fact that the 2026 Olympics are taking place in two different cities.

From tech platforms to candy companies, here’s how some of the highest-ranking brands earned their spot on the list.

The “Khol” ring, our Piece of the Week, transforms the traditional Indian Khol drum into playful jewelry through hand-carved lapis.

The catalog includes more than 100 styles of stock, pre-printed, and custom tags and labels, as well as bar code technology products.

The chocolatier is bringing back its chocolate-inspired locket, offering sets of two to celebrate “perfect pairs.”

The top lot of the year was a 1930s Cartier tiara owned by Nancy, Viscountess Astor, which sold for $1.2 million in London last summer.