The History Behind … The Squash Blossom Necklace

The latest installment in our antique jewelry series examines the iconic Native American design.

A necklace crafted in silver and turquoise consisting of round silver beads interspersed with beads that look like they are blooming, all leading down to what looks like a horseshoe or, some would say, a crescent moon turned on its side.

Who were the first to make these necklaces that we know as squash blossoms and where did they get their name? (Hint: It is from a fruit, though maybe not the one you have in mind.)

To learn more about the design, National Jeweler spoke with two experts on the subject: Lois Sherr Dubin, author of a number of books about Native American jewelry including “North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment” and “Jesse Monongya—Opal Bears and Lapis Skies,” and Joseph Tanner and his daughter, Emerald. The Tanners own Tanner’s Indian Arts in Gallup, New Mexico, and have a private collection of squash blossom necklaces.

Here’s what they had to say.

When were the first squash blossom necklaces made?

While squash blossom imagery can be found in petroglyphs (rock art) that pre-date European contact in the Southwest, Dubin said the squash blossom necklace was created in the late 1870s or early 1880s after the native people of the area made contact with Spanish Mexicans.

The Navajo, it is believed, were the first tribe to adopt the design, but by the early 1900s, the art form had spread to neighboring tribes, including the Zuni and the Pueblo.

Native Americans had plenty of their own jewelry before they made contact with the European settlers, yes, but, “This particular art form … was really European-influenced,” she said.

So, we call it a “squash blossom” necklace. Where did that name originate?

The actual origins of the name are “a little loose,” Dubin said.

The name of the necklace really grew out of the one type of bead that was, as mentioned above, developed by and credited to the Navajo, and whose name in the Navajo language translates to “bead which spreads out,” Dubin said.

While the entire necklace has taken its name from one type of bead, the classic squash blossom necklace actually has three distinct parts: the plain round beads; the round beads with the “petals,” so to speak; and the horseshoe-like pendant at the bottom called the Naja.

There is a lot of scholarly discussion around the topic, Dubin said, and there are two competing beliefs about the origin of the name “squash blossom.”

Some say that the Navajo created the squash blossom after seeing the pomegranate design frequently used as decoration by the Spanish people, including on the buttons of the soldiers’ uniforms. (In parts of Spain, the pomegranate is a revered fruit; in particular, it is the heraldic symbol of the city of Granada, which is also the Spanish word for the fruit known in English as pomegranate.)

Others, meanwhile, believe that the squash blossom is exactly as advertised—a design taken from the flowery part of the squash plant, which, along with corn and beans, are the crops that Native Americans relied on in the Southwest.

“These are native plants that they would see the importance of, and I am of the belief that most native work has meaning behind it, at least originally,” Dubin said.

Regarding the plain round beads, does the number of them in between the squash blossom beads hold any meaning?

No, Dubin said, it’s arbitrary: “There’s nothing other than the artist’s wish to make it more or less elaborate.”

Aside from the beads, the necklace also has another part, the Naja. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

“Naja” is the name the Navajo gave to a symbol believed to have originated in the Middle East in ancient times. Like some many symbols, it was created as a talisman for protection, with the Moors affixing it to their horses’ bridles to ward off the evil eye.

It ended up as the centerpiece of the squash blossom necklace in one of two ways, Dubin said.

Either the Navajo saw it on the Spanish Mexicans, or it came to the Southwest through the Plains people, the Shawnee or the Delaware. “Again, that’s unclear,” she said. “But the point is, the form itself has ancient origins.”

In early examples of squash blossom necklaces, the Najas are strictly silver, but later Native Americans began adding turquoise and even coral to them as the design evolved over time, Joe Tanner said.

He added that the Naja is also representative of the womb, and when a squash blossom necklace features a single turquoise nugget suspended from the Naja, it is often interpreted to be symbolic of a child in the womb.

While the necklaces do not have a specific ceremonial use, they were worn as a symbol of one’s status, wealth and cultural belonging.

And the bigger, the better, Dubin said: “You wore your wealth in these cultures—you wore your silver, you wore your turquoise.”

The jewelry the natives made for themselves was big and bold, employing big chunks of turquoise and heavy-gauge silver (see Della Casa Appa’s immense squash blossom necklace above), though the artists tended to scale it down when creating jewelry for tourists and non-natives.

As noted, squash blossom necklaces primarily were crafted in in silver and turquoise. Is that because these were the materials that were readily available to the Native Americans, with the silver coming from Mexico?

Dubin said actually, Native Americans originally used the American silver dollar for their necklaces, doming two coins and then soldering them together. After the government decided they didn’t want coins being used as jewelry materials, they started using sheet silver.

Tanner said the early squash blossom necklaces used what is called “First Phase”-style silversmithing and have a more rustic look to them.

“But (it was) still way ahead of its time,” he noted. “The Native American artists of that time were hand-fabricating jewelry before they had all the tools that contemporary artists today have.”

Gemstone-wise, turquoise was, and still is, a very sacred stone in the Southwest. This is because, first of all, it’s a local stone that comes from “Mother Earth,” Dubin said, and though it originates in places with an arid landscape, it is blue, like water and the sky that brings water.

“It’s just the native beloved stone, a sacred stone,” she said. “You’re not Navajo, you’re not Southwest without your turquoise.”

Joe Tanner added that though some gemologists and designers prize the clean, clear, robin’s egg blue turquoise from mines like Sleeping Beauty over stones with a heavier matrix, that’s not the case among Native American designers.

“The old medicine priests in the Southwest say if it doesn’t have the matrix and spider-webbing, then it doesn’t carry that extra strength that (they believe) these patterns bring to the gemstone,” he said.

While turquoise was the main gemstone used, squash blossom necklaces with other gemstones, including coral and mother-of-pearl, can be found.

When was this style at the height of its popularity?

According to Dubin, the squash blossom necklace peaked in the early 1970s, when the bohemian fashion trends of the time begat a turquoise craze.

“There was a frenzy of buying turquoise in the ‘70s in the Southwest, and what was swept up in that were squash blossom necklaces that were heavily inlaid with turquoise,” she said. “And then it kind of subsided a bit.”

But the style never completely disappeared, and while it’s not a prime art form today, it’s considered traditional, and many modern Native Americans designers still pay homage to the style.

Joe Tanner said he sees demand for squash blossom necklaces from a younger generation.

“Part of the reason that it’s so popular in the current retail market is that millennials buyers, they like their jewelry to look handmade,” he said. “They’re going for these more First Phase-style looks so it has the appearance that it is handmade, even in cases in which it is not.”

The Latest

Associate Editor Natalie Francisco highlights her favorite jewelry moments from the Golden Globes, and they are (mostly) white hot.

Yantzer is remembered for the profound influence he had on diamond cut grading as well as his contagious smile and quick wit.

The store closures are part of the retailer’s “Bold New Chapter” turnaround plan.

How Jewelers of America’s 20 Under 40 are leading to ensure a brighter future for the jewelry industry.

Through EventGuard, the company will offer event liability and cancellation insurance, including wedding coverage.

Chris Blakeslee has experience at Athleta and Alo Yoga. Kendra Scott will remain on board as executive chair and chief visionary officer.

The credit card companies’ surveys examined where consumers shopped, what they bought, and what they valued this holiday season.

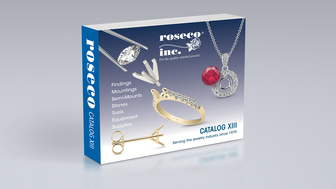

Roseco’s 704-page catalog showcases new lab-grown diamonds, findings, tools & more—available in print or interactive digital editions.

Kimberly Miller has been promoted to the role.

The “Serenity” charm set with 13 opals is a modern amulet offering protection, guidance, and intention, the brand said.

“Bridgerton” actresses Hannah Dodd and Claudia Jessie star in the brand’s “Rules to Love By” campaign.

Founded by jeweler and sculptor Ana Khouri, the brand is “expanding the boundaries of what high jewelry can be.”

The singer-songwriter will make her debut as the French luxury brand’s new ambassador in a campaign for its “Coco Crush” jewelry line.

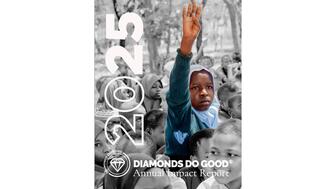

The nonprofit’s new president and CEO, Annie Doresca, also began her role this month.

As the shopping mall model evolves and online retail grows, Smith shares his predictions for the future of physical stores.

The trade show is slated for Jan. 31-Feb. 2 at The Lighthouse in New York City's Chelsea neighborhood.

The annual report highlights how it supported communities in areas where natural diamonds are mined, crafted, and sold.

Footage of a fight breaking out in the NYC Diamond District was viewed millions of times on Instagram and Facebook.

The supplier has a curated list of must-have tools for jewelers doing in-house custom work this year.

The Signet Jewelers-owned store, which turned 100 last year, calls its new concept stores “The Edit.”

Linda Coutu is rejoining the precious metals provider as its director of sales.

The governing board welcomed two new members, Claire Scragg and Susan Eisen.

Sparkle with festive diamond jewelry as we celebrate the beginning of 2026.

The master jeweler, Olympian, former senator, and Korean War veteran founded the brand Nighthorse Jewelry.

In its annual report, Pinterest noted an increase in searches for brooches, heirloom jewelry, and ‘80s luxury.

Executive Chairman Richard Baker will take over the role as rumors swirl that a bankruptcy filing is imminent for the troubled retailer.

Mohr had just retired in June after more than two decades as Couture’s retailer liaison.